The Glowing Legacy of Gyula Kosice

Gyula Kosice would have been 100 years of age in 2025, had he not passed away at the age of 92 in Buenos Aires, Argentina—the country where he grew up, became an artist, and rose to fame. Who was Kosice, and which groundbreaking developments in 20th-century art did he help to shape in a decisive way?

by

Claudio Vogt

The story begins in what was then Czechoslovakia. In 1924, Ferdinand Fallik was born in Košice, where he lived with his parents and two brothers until he was four years old. In 1928, the family emigrated to Argentina aboard a steamship. As a tribute to his origins and his birthplace in what is now Slovakia, the artist later adopted the name Gyula Kosice and embarked on a remarkable career as a sculptor, theorist, and poet.

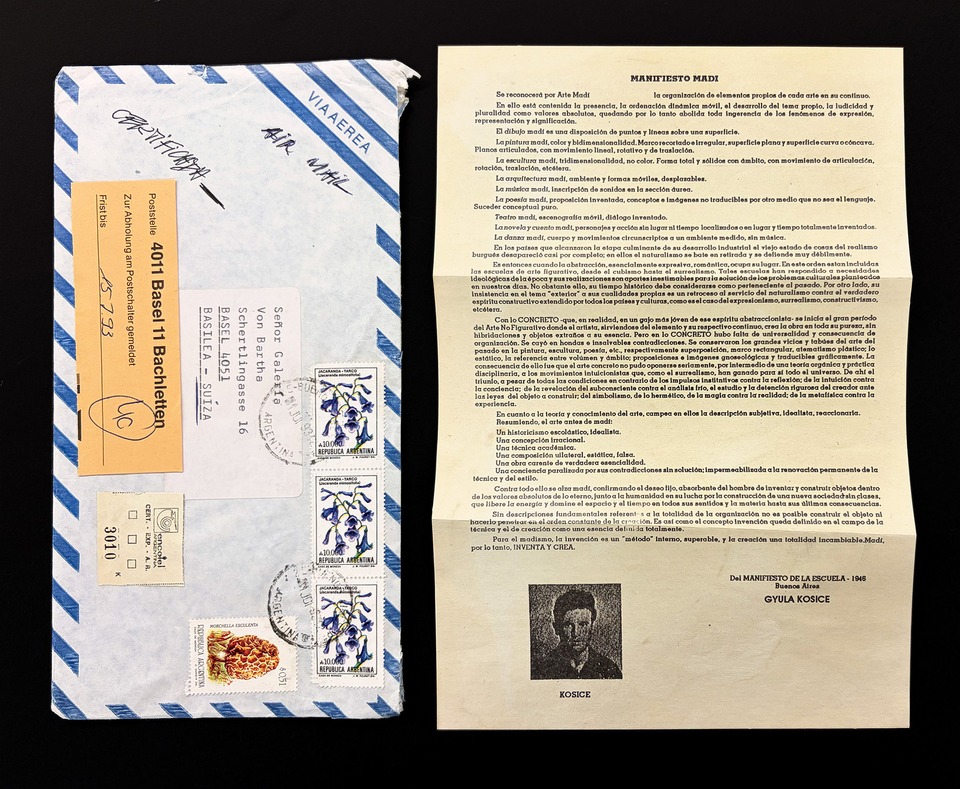

Already in the 1940s, he was part of the circle of avant-garde artists who played a key role in spreading and developing abstract art in Argentina. In addition to publishing the influential magazine Arturo (of which only a single issue was published) and co-founding the Grupo Madí with Carmelo Arden Quin and Rhod Rothfuss, Kosice was drawn to unconventional artistic practices. At just twenty years old, he began experimenting with sculpture, driven by a desire to free the medium from rigidity and set it in motion. In his view, art should be dynamic, in motion, tactile, and foster a relationship between viewers and the artist. This may also explain why, in 1946, Kosice began working on something spectacular, something at the time only known from advertising: thin, glowing tubes shaped into lettering or simple silhouettes, now widely known as neon.

It is likely that Kosice was one of the first, if not the first, artists to create artworks using neon tubes in such a manner. An extraordinary achievement, considering how this material would later be brought to great prominence by artists such as Tracey Emin, Dan Flavin, Lucio Fontana, Jenny Holzer, and Bruce Nauman.

Tracey Emin, “I could have really loved you”, 2007

Dan Flavin, "untitled (to my dear bitch, Airily) 2", 1984, at Kunstmuseum Basel, 2024.

Courtesy The Dan Flavin Estate, David Zwirner. Photo: Florian Holzherr

Lucio Fontana, struttura al neon per IX Triennale di Milano, 1951/2017, at Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, 2017. Courtesy Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Fondazione Lucio Fontana. Photo: Agostino Osio

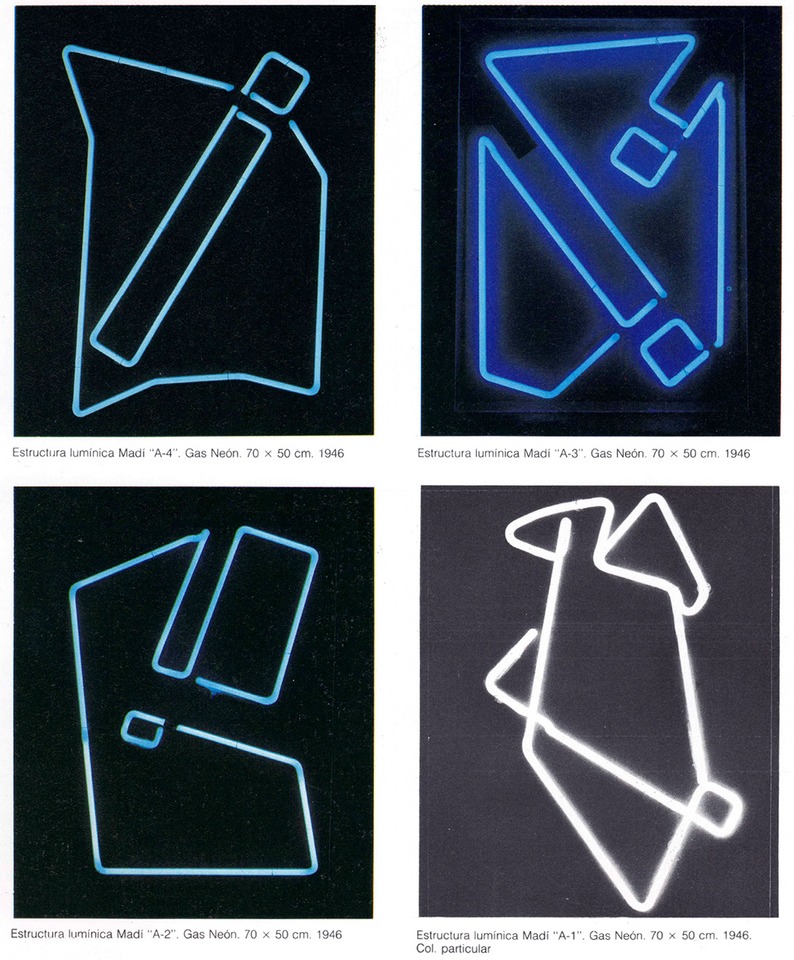

In the literature, four very early works by Kosice can be found: the series Estructura Luminica Madí, designated A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4. Inside the four plexiglas boxes, each measuring 70 × 50 cm and created in 1946, simple geometric patterns glow: forms that resist clear description. In retrospect, they seem as if the cobalt-blue light tubes are still in the process of finding their form, like a butterfly about to emerge from its cocoon. And so, in these early works, the birth of a new art form is already inscribed.

Kosice continued the Estructura Luminica Madí series in the years to come. The sixth variation, for example, was recently shown at the Pérez Art Museum Miami in a major exhibition marking Kosice’s 100th birthday. It is part of the Houston Museum's collection, while comparable works can be found in the collections of major institutions such as the Centre Pompidou, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, and the Musée de Grenoble.

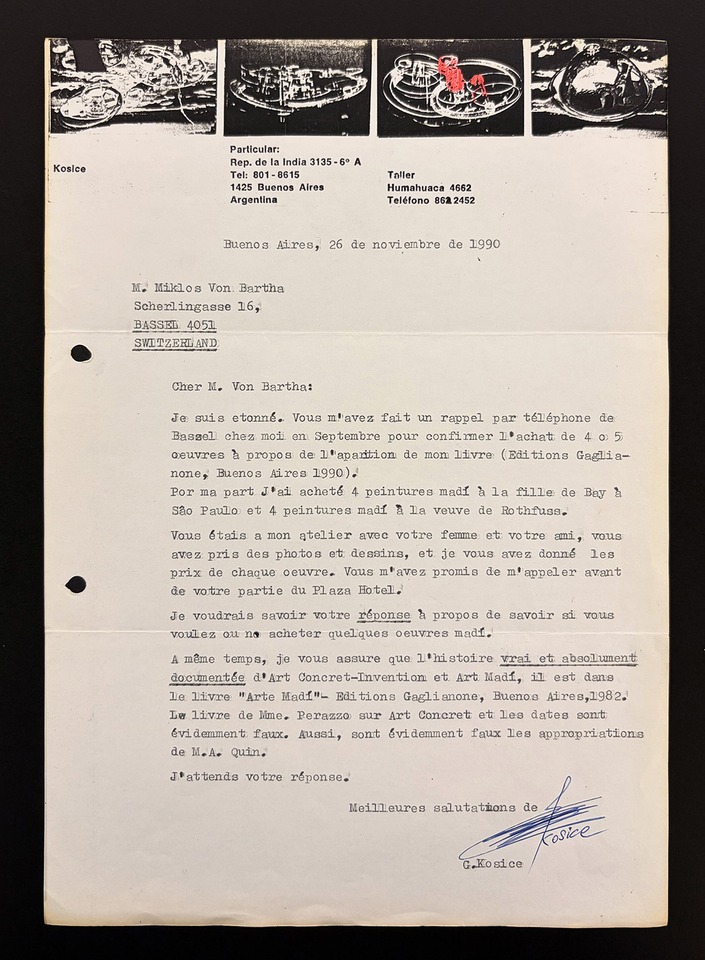

Why, then, is von Bartha presenting such an important work at Art Basel in Miami Beach, and how did the gallery acquire this historic piece? To answer that, we must go back in time. In 1989, Miklos von Bartha traveled to Argentina to visit the studios of the most important living artists of the Arte Madí and Arte Concreto movements. During this trip, he also met Kosice and brought back to Europe works from various studios, including two “brilliant and epoch-making neon pieces” (as Miklos von Bartha put it), among them Estructura Luminica Madí, A-4. Since then, the work has remained in private ownership in Switzerland.

It therefore seems only fitting that this piece is now being shown on the continent where it was created, long before neon art conquered the world and continues to captivate people to this day.

Header Image: Gyula Kosice, scanned from the publication “Kosice. Arte y Filosofia Porvenirista,” 1996.